To say that last year wasn’t my best year as a beekeeper would be a massive understatement. I lost two of my hives mid-fall after winterizing them, and, even after trying a different winterizing method I lost the third sometime in January.

After that I seriously considered whether or not I should have bees on the farm, because as much as I like to take on newer and bigger challenges– and as much as I genuinely love having bees on the farm– I also feel strongly about only taking on responsibilities that I can give the appropriate time and energy to. Particularly when those responsibilities mean, you know, keeping things alive.

One of the most difficult things about beekeeping (and a lot of things on the farm) is the extended learning curve. If you screw something up, it’s difficult to immediately recognize and identify exactly what went wrong, and usually you won’t be able to correct and/or attempt something different for an entire year. (And even then, the new thing you try might not work.)

As someone who likes to try and master things immediately, it’s maddening. And it also means that “learning” can feel a lot like “failing” for a much longer period of time than I’m used to. So the big question for me was, am I completely out of my depth and failing at this, or am I actually slowly learning and becoming a better beekeeper?

The truth is, I don’t know yet… two years of beekeeping (and two winters) just isn’t enough time to answer that question. So after a lot of debate (and encouragement from all the beekeepers who commented on my last couple of bee-related posts) I decided that I would invest another year in the beekeeping learning curve, and if my two new colonies don’t survive this winter then I’ll wait until I have more time to invest in classes/mentors (and to just be on the farm) before I start any new hives.

Here’s where I started this year: Three dead hives out in the yard, and only guesses as to what happened (and whether or not it was safe to use that equipment for new bees.) So, I did an autopsy.

Actually I did a lot of research on how to autopsy a colony first. Here are some of the resources I used:

- How to Autopsy a Bee Colony on BeverlyBees.com

- Clean Up of Hives That Didn’t Survive on KelleyBees.com

- This Colony Postmortem (and response) on Honeybeesuite

- Several chapters of The Hive and The Honeybee from Dadant (Literally the largest book I own.)

Going in to this I had a few thoughts, but mostly a lot of questions. For the two hives that died in fall after I winterized them (with too much ventilation) my thoughts were:

- I’d created too big of a space at the top of the hive and yellow jackets got in and killed all my bees (after research that seems unlikely unless the colonies were extremely weak from varroa mites)

- The ventilation space was too great and the bees got too cold

For the third hive, I had to assume it was cold-related (or possibly something defective about the quilt-box I built to winterize them.)

Here’s what I found when I opened the hives:

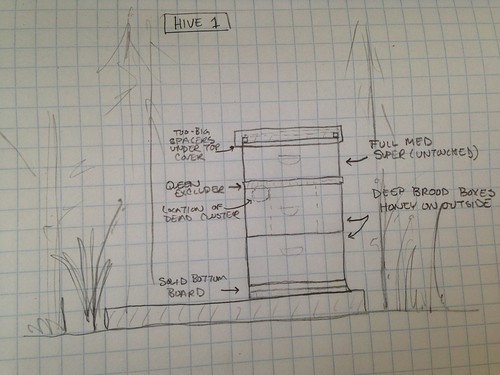

Hive 1: Originally established in 2015, successfully overwintered in 2015/2016, produced 2 med supers of honey and one shallow super of cut-comb in 2016, died Oct 2016 the 3-4 days after I winterized the hive.

When I winterized in mid-October I noticed there was some honey in the top brood box, but the center frames were empty, so I left a full honey super on top of the hive. I’d read that if you leave a full honey super on the hive, the bees will move the honey down deeper into the brood boxes to be used as winter stores, although I’m now skeptical of that.

Here was the setup:

Here’s the tiny cluster I found when I opened the hive:

Some things to note:

- This cluster is tiny, and would not have been able to survive the winter. These are Italian bees which typically have a very large (basetball sized) cluster, according to my research.

- The frame they died on is almost completely empty of honey.

- There was plenty of honey two frames over, and one frame up BUT I’d left the queen excluder on, expecting that the bees would move the honey from the super down deeper into the hive and that I would remove that top box before “winter” really hit.

Conclusion: This hive died of starvation/cold, but with these numbers likely could not have survived the winter regardless. The big question for me is why there are so few bees, when the hive had been full when I winterized it (and there seemed to be a lot of dead bees outside of the hive in fall when I’d realized what had happened.) The fact that there was a ton of honey left in the hive leads me to conclude it wasn’t yellow jackets or other robbers (or that honey would be long gone.)

There is one scene from this hive that makes me feel like freezing was the final blow for these bees…

This bee was at the opposite end of the same frame the cluster died on. She died mid-stride, basically, while pulling the cap of one of the cells full of honey. A moment frozen in time… I think probably literally frozen with a blast of cold air.

Key Learnings: Rotate frames full of honey to the middle of the hive in mid-fall, always remove the queen excluder when leaving honey on the hive for winter, and modify all frames to include the “bee highway”. The farmer I get my bees from suggested removing a corner of the foundation when putting frames together so that bees could easily access the next frame without climbing up and over a frame. I did that for many of my frames, but I’d also bought more equipment that didn’t come with the corners removed and figured the “bee highway” was a nice-to-have but not critical.

Now I’m thinking that, with honey 2 frames away, these bees might not have starved if they had access to the honey without needing to move up and over the frames.

Still, the hive seems weak and likely wouldn’t have survived if I’d done those things right, so maybe the biggest learning for me is researching and figuring out how to determine the strength of a hive in late summer/ early fall.

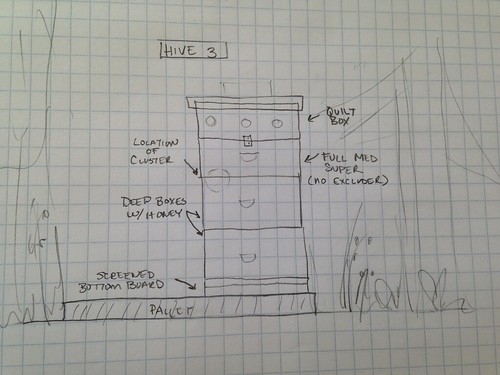

Hive 3: Established spring 2016, produced 1 med super of honey, winterized in November with quilt box, died Jan 2017

I was taking no chances so this hive was winterized with two deep brood boxes and 1 med super full of honey, plus the quilt box on top.

When I removed the quit box, the shavings were completely dry, but it looked like there had definitely been some moisture at some point…

The main “cluster” of bees was located at the top of the second brood box, in one of the outer corners, and this is what it looked like when I pulled it out of the hive…

Some things to note:

- The bees in the center of the cluster are very decayed. There is a virus called chronic bee paralysis virus, which leaves bees looking dark, greasy, and hairless, but it typically doesn’t kill a hive and only the center of the cluster had this particular look.

- The cluster itself is a decent size for Carniolans (I’ve read a softball-sized cluster is normal.)

- There was no overwhelming evidence of varroa (on bee bodies or in the hive)

- There’s capped honey all around the cluster indicating they didn’t die from lack of accessible food

I also noticed a few queen cells (these are larger cells bees create to raise a new queen… generally indicating the hive has swarmed or is planning to.)

And I also noticed that there were some squatters living under the screened bottom board…

Mice can definitely destroy a beehive by eating all the stored honey, but these two didn’t have access to the inside of the hive, just the spot under the bottom board. I haven’t found anything that suggests a mouse can transmit or kill bees just by living in close proximity, so this probably isn’t the culprit (but I told them to take a hike anyway.)

Conclusion: I think my original guess– that they died strictly from the cold– is accurate. Given the evidence of moisture on the quilt box, and the way the bees decayed (as if they were wet) I think that either the quilt box didn’t do it’s job (and moisture built up inside of the hive and dropped back on the bees) OR that moisture somehow came in through the quilt box itself (perhaps through the ventilation holes on a cold/rainy day?) My other thought is that the screened bottom board my have contributed to this (even though I had the bottom well-blocked against snow and drafts.)

Key Learning: I don’t think I’m going to use a quilt box again this year, and I may try other winterizing techniques like creating solid wind-breaks and using tar paper on the outside of the hive.

Overall, not a fun task, but I do think I learned a bit more about my hives and how to better prepare for winter this year. Also, my mudroom now looks like this…

There is honey everywhere.

Because I didn’t find any evidence to indicate the honey or equipment is unsafe, I’ll feed some of this back to my new bees… but it still leaves a hell of a lot of honey to extract.

However that’s a project for another day, because my first priority over the weekend was getting the new bees into their new homes. And, luckily, I had a couple of helpers…

These are my cousins who inspired the idea of Farm Camp. They came up for the day and learned a little about bees (and how to pick locks, and how to build wood boxes… and also taught me how to make slime! It was a full day.)

It was probably the minimum temperature I felt comfortable installing bees (around 55 degrees in the sunlight, and pretty windy, with lows below freezing over night) but it was the best I was going to get according to the forecast, so we waited until the wind died down and then got their hives (with plenty of syrup and a few full frames of honey to make sure they were good to stay inside for the next few days.)

Almost immediately after they were in the hive, my mom –who was not the biggest fan of bees a few years ago– said, “It’s so nice to have them buzzing around the hives again.” And it really is. Bees bring added life and vibrancy to the farm, and I’m really glad I made the decision to stick with this for another year.

Article reference Adventures In Beekeeping: Autopsies and New Colonies

No comments:

Post a Comment